Along with an estimated 65 other genera, Philadelphus is a genus split between Asia and the Americas, with elements migrating north from Eurasia when the continents divided. Species developed independently, with good ability to adapt to the changing climatic and geological conditions. New species of Philadelphus are still being discovered today in the mountains of northern Mexico, for example, with new plants growing in various collections from recently collected seed.

Phildelphus species often have few clearly distinguishing characteristics, and attempting to sort them out can lead to a serious risk of brain damage, their disposition to mate with anything similar nearby adding to the taxonomic and nomenclature problem. The cultivars, though, are a different story – offering a wide range of clearly different flower forms and habits. What follows attempts to introduce this range.

There is a single species native to Europe, P. coronarius, the old ‘Mock Orange’ that has famously added fragrance to many a midsummer marriage bouquet. But the Philadelphus of garden history is otherwise mostly a mongrel race, largely consisting of either spontaneous hybrids, or hybrids skilfully created by the French genius Victor Lemoine, who we also have to thank for many other ornamental popular shrubs, dating back to his first hybridising endeavours in the 1880s. Standout garden varieties of Philadelphus bred by Lemoine include the reliably superbly-scented ‘Belle Etoile’ (featured above) ‘Coupe d’Argent’, ‘Voie Lactée’ (Milky Way) and many others. Some disappeared after going out of fashion and are only recently being rediscovered in private gardens and repropagated (for example, by the National Trust, who came to White House Farm recently to replace some of the early 20th century Philadelphus plantings across their properties nationally).

Lemoine produced his Philadelphus hybrids by crossing species (his earliest was P. coranarius x microphyllus to produce P. x lemoinei), then crossing hybrids with hybrids, with a complex parentage that led to many of the most effective cultivars for our gardens. He has produced the majority of philadelphus cultivars we grow today.

Philadelphus cultivars have the big advantage of flowering at midsummer, when the big band spring displays are over. They are brilliant companions to roses, being white flowered and thus flexible in their use, to contrast for example with reds, or cosy up to pale pinks. Their fragrance, which is more free in the air than most roses, can subtly compete and contrast. To wander in a warm summer garden at dusk, ‘as light thickens, and the crow makes wing to the rooky wood’, with not a breath in the trees, through pools of Philadelphus perfume, is a joy and a privilege.

Philadelphus are tolerant of soils of any pH and structure, and tough and hardy in low temperatures. They vary in habit from 6 metre monsters to half metre dwarfs, their flowers ranging from big untidy doubles to exquisitely cupped four-petalled singles, in racemes or panicles, offering gardeners wide variety – and versatility – of use. The earliest flower from the last week of April or beginning of May (P. schrenkii) and the latest not until mid-July (P. incanus) with the majority at their best in the middle of June, when more time is spent in the garden than at probably any other time.

Out of flower, Philadelphus are just a bunch of green foliage, but the larger types are robust enough, for example, to host late flowering clematis or scrambling informal roses; varieties of Philadelphus of modest habit shrink into the background unseen.

Remarks on a few cultivars follow: I have included some that can be sourced with some effort, but which are not frequently seen in gardens.

Double flowered cultivars

Of the doubles, ‘Virginale‘ is often encountered, but I find her rather stiff and leggy, tall and angular – as Howarth-Booth puts it, ‘whose buxom appearance suggests a rather fuller life than the French adjective conveys’ (Effective Flowering Shrubs, p.238). ‘Mrs E. L. Robinson‘ is not very different, though thought by some to be a notable improvement. ‘Minnesota Snowflake‘ is a hearty 2m double, bred in the US for hardiness. Bold and free, it makes a good background plant. ‘Girandole‘ is another large, spreading double that needs space.

Preferable, in my view, is ‘Enchantement‘, of more modest bushy growth, to a bit above 2m, with a fuller figure, and free-flowering clusters of double flowers on arching branches. A more compact double is ‘Natchez‘, named after a town in Mississipi. The relatively compact bush is rather tousled, and the doubled flowers untidy, with rows of narrow petals surrounding a few stamens. Both its habit and flowers remind me of the Ogden Nash limerick:

There was a young belle of old Natchez,

Who ripped all her garments to patches.

When comment arose on the state of her clothes,

She drawled ‘when ah itches ah scratches’…

The flowers on ‘Natchez’ are unusually large, held singly or in small clusters with a small bunch of stamens displayed on a modest bush; it has definite character and appeal.

‘Conquete‘ is somewhat similar, but with even more congested and rather unkempt narrow-petalled flowers.

In contrast, ‘Boule d’argent‘ is neat and dapper, both in habit and flower, reaching not more than 1.5m, with tight ball-like clusters. I lost my plant to honey fungus, so if anyone could provide cuttings they would be gratefully received and happily exchanged.

‘Dame Blanche‘ is a small plant to about 1m, with semi-single flowers and a few petaloids – another good choice where space is limited.

Rarely seen, ‘Ophelie‘ is another Lemoine hybrid, its semi-double flowers with a few petaloid processes in the centre, along with a small purple stain at the base. The habit is excellent, semi-weeping and nicely balanced. As it is unlikely to exceed 1.25m, it’s perhaps worth a place as a lawn specimen.

Single-flowered cultivars

Of the smaller singles, ‘Sybille‘ is exquisite, a shapely squarish flower, slightly fringed and prominently stained with purple at the base. It is a twiggy, dense, 1.25m shrub – another good choice for a small garden.

Cultivars in the Lemoinei group are generally of modest size. The type (‘Lemoinei’) has arching branches heaped with simple single flowers on a dense but neat bush to about 2m, and is particularly fragrant.

‘Avalanche‘ (below) is one of my favourites, late, spreading, low, elegant, fragrant (beware imposters).

‘Silberregen‘ , a modest self-contained shrub, smells strongly of strawberries.

‘Manteau d’ermine‘ is one of the smallest at about 0.75m with clusters of cream double flowers. There are more. ‘Lemoinei ‘, crossed with the dubiously hardy Mexican P. argyrocalyx, is a very rare upright bush with elegantly pendulous shoots, showing to advantage the prominent silver calyxes to its cupped white flowers, that came to us from the National Collection at Leeds. I have given this a ‘kennel’ name of ‘Silver Cascade’. It is not registered.

Some new Mexicans

Some recent introductions from Mexico that have proved their worth in the garden are forms of P. maculatus, with single drooping flowers with a purple eye (‘blotched’ or ‘stained’, as the name suggests) and among the most fragrant of any flowering shrub. ‘Sweet Clare‘, a form I named for my daughter, and ‘Mexican Jewel’ are similar, the former being perhaps the most strongly fragrant of all Philadelphus.

P. palmeri, a new Mexican species I introduced from John Fairey seed, is a low shrub, arching nicely, but with me, of still unproven hardiness. Such new species have yielded quite a few new hybrids which look very promising, but as yet with me are unproven. Keep an eye open, for example, for ‘Fragrant Falls‘ and ‘Pearls of Perfume’. More are coming onto the market.

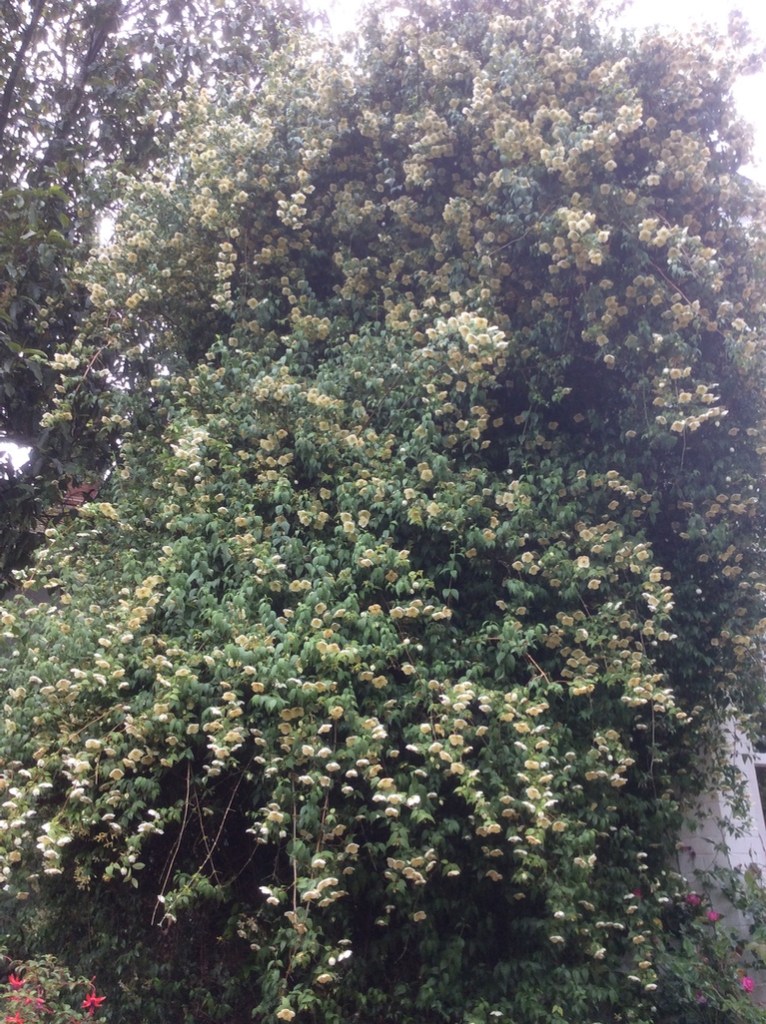

Many other Mexicans are vigorous scramblers, that shown a tree, will be 15ft into it in no time, and may well continue to 25ft, long raking shoots eventually hanging down wreathed in flowers to spectacular effect. P. sargentiana is one such, its large fringed flowers crowded on long stems (another plant from John Fairey seed established here at White House Farm).

An old variety with similar climbing instincts is P. ‘Rose Syringa‘ which pushes up a wall to the eaves of the house, its long shoots falling with the weight of myriad squarish fragrant yellowish/cream flowers with a purple stain. In full flower this is a spectacular plant, of uncertain origin. Bean gives a good account of it.

Purples and pinks

There is another group based on a Lemoine plant with a more prominent purple eye, P. purpureomaculatus – of modest growth with arching branches and set with flowers, as the name suggests, deeply stained with purple. ‘Belle Etoile‘ and ‘Sybille‘ (above) are grouped here, and the latter is itself a parent of ‘Beauclerk’, which displays to great effect a large flat flower about 2” across, with an area of light pink at its base, on a medium sized bush. There’s also ‘Bicolore’ and ‘Burkwoodii‘ which I have less experience of growing.

A spectacular new introduction created by Alan Postil, former propagator at Hilliers, to create a genuine pink effect, was voted plant of the year at Chelsea 2025. Its title is more a story than a name – ‘Petite Perfume Pink‘ leaves little to add in its description. The basal bright pink stain suffuses into the petals to give a true pink; ‘petite’ describes the habit which is compact and arching; ‘perfume’ speaks for itself. It is a breakthrough plant.

Moving up a space in size, there is a multiple choice. Leaving aside the iconic and ubiquitous ‘Belle Etoile’ – a familiarity it fully merits, and still my choice, if I could only grown one Philadelphus – there is ‘Voie lactée‘ (Milky Way) with quite broad petals, which reflex slightly on maturity, with a small and narrow bunch of stamens at the centre.

Splendens is a less well-known, huge, 4m spreading, arching plant of notable grace, in spite of its size. The flowers are in numerous weeping panicles along the lateral branches, creating a waterfall of slightly fragrant elegance. There was a magnificent specimen in Maurice Mason’s arboretum in Larch Wood which he had from Hilliers; but despite being an easy grower it is a plant rarely seen, perhaps because of its size.

‘Atlas’, another Lemoine hybrid, is a rather informal large shrub with large flowers over 2” across – and often an alias for various plants found under this name.

‘Coupe d’argent‘ is little planted, but its large squarish fragrant flowers that mature flat in spite of its name, with a hint of purple at the base, are magnificent. Its habit, though, is excruciating, spraying long gangling shoots in every direction – but ours does very well trained into a tree, and tumbling over an arbor.

P. delavayi is the dominant species of Philadelphus in W. China, frequent and widespread. It flowers early in cultivation, is very fragrant, with panicles of shapely white flowers contrasting with its dark calyxes. The best known for this character, with a very dark purple calyx, is P. delavayi Nymans Variety. The habit is stiff, upright, then spreading, growing to 3m, but still striking in full flower. At the other end of the scale is a cultivar of P. delavayi known as ‘Flavescens’, with a distinct yellowish cream calyx.

Variegated Philadelphus

For those who enjoy variegated plants, there are a couple of choices: ‘Variegatus’, a form of P. coronarius with a very bold cream variegation, the principal effect of which is cream, with the ratio of cream to green strongly in favour of the former, to the point where the flowers tend to merge. ‘Bowles Var‘ is synonymous. Quite different in both habit, variegation and flower is ‘Innocence’. The variegation consists of yellow flecking on a deep green base. The multiple flowers are nicely cupped and presented on an upright shrub to around 2m. It is a distinctive plant that rarely reverts to green.

These are just a few Philadelphus in our collection. There are many more. We used to grow more than eighty, but have discontinued some, mainly those that were bred for hardiness rather than for flower, so of more limited ornamental value. Comments on cultivars are of course personal opinions. I have omitted the more than sixty odd species for the most part; but I hope I have sufficiently illustrated the range, variety and versatility of a genus that should be more thoughtfully considered when making planting choices.

Help for making such choices should be soon at hand, because an RHS AGM trial of the more compact cultivars is at the planning stage. This will be on display at Wisley and will showcase a good representative selection of the best for overall garden value, particularly for the smaller garden.

Maurice Foster Sept 2025