Maurice is on last week’s ‘Gardening WithThe RHS’ podcast, talking about hydrangeas: listen here.

In Asiatic Magnolias in Cultivation (1955) G. H. Johnstone OBE VMH wrote:

“ This magnolia [sargentiana var robusta] is certainly one of the most spectacular of all those introduced into our gardens and in the running maybe for inclusion in a list of the most beautiful plants to be seen in the gardens of the British Isles.”

George Johnstone grew all the big Asiatic magnolias in his garden at Trewithen in Cornwall, and studied them as living specimens closely and comprehensively over many years at first hand. He was also a frequent visitor to the other great Cornish collections, notably to that at Caerhays, where J. C. Williams had planted all the big Asiatic species available at that time, including the type species of M. sargentiana. This appeared more closely allied to M. dawsoniana than to var robusta, and there is a remarkable similarity in flower between the two, the relatively narrow tepals hanging loosely ‘like the fringe of a tassel’.

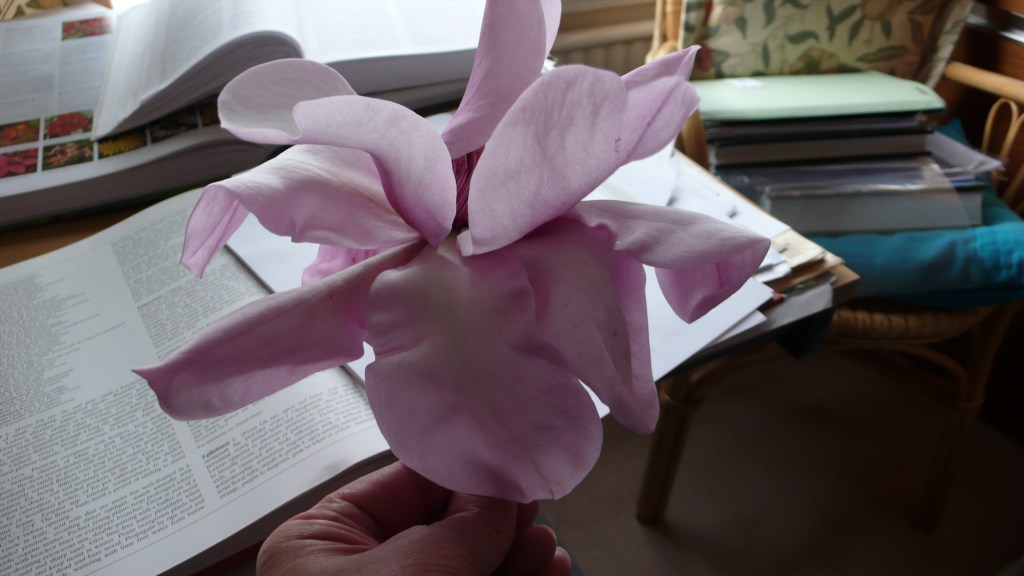

By contrast, the bigger nodding flowers with large broad tepals of var robusta are just one character that singles it out as a distinctive plant, very different to the type species.

M. sargentiana var robusta was found and introduced as a single plant by Ernest Wilson (W 923a) on the Washan in W Sichuan. He collected it blind in a population of the type without seeing it in flower., which may have influenced his naming.

Both Johnstone and subsequently Treseder (Magnolias) were both firmly of the view that M. sargentiana var robusta merited full species status. In his book Treseder lists the detailed differences between M. sargentiana and M. sargentiana var robusta. Without reproducing all his comparative detail here, suffice it to say that Treseder clearly differentiates habit, young shoots, leaves, flower buds, flowers, fruit cones, and seedling flowering times (25 years for the type, and only 11-15 for var robusta).

Johnstone makes the point that of the many seedlings of var robusta raised over the years in Cornwall, none reverted to the type, all maintaining the character of the original. My own experience is limited, but I have been growing what is known as the ‘Caerhays Dark Form’ for 50 years from an original Treseder graft, which today as I write is pushing 50ft with perhaps 2000 flowers. It is a spectacular tree (see below).

I sent seed to the late Peter Chappell who returned a seedling that had beetroot red young growth, which needless to say it lost as it matured. It flowered in 11 years from seed and is identical to the parent in every particular, so that cut flowers from the two, in different vases were indistinguishable by visitors who could not tell which from t’other. I like to think that the ability to reproduce morphologically identical offspring is a strong indicator of a true species.

The change to full species status was not accepted by the botanical authorities at the British Museum and the RHS Council at the recommendation of the then acknowledged authority on Magnolias, J E Dandy, who wrote ‘ I….cannot accept that this single plant (from which all the cultivated plants are derived) represents a botanical taxon.’ In other words a single plant growing within the range of typical M sargentiana is not enough to establish a new species.

This naming of a less common and less horticulturally significant variety as the type species is an example of a problem that is by no means unique, especially when opinions are based, for example, on herbarium specimens only (Callaway, in The World of Magnolias points out that Dandy named at least 6 magnolia species based on single herbarium specimens.)

None of the authors above followed through, deferring to the botanists. They reluctantly concluded that more should be known about the plants involved with more specimens studied in and from the wild. Treseder sums it up ‘ The unfortunate difference of opinion between plantsmen and botanists remains and is likely to continue until botanical research becomes possible once more in China’.

Unfortunately since China opened up again to western botanists in 1980, as far as I am aware no new introductions or further studies of M. sargentiana or M. sargentiana var robusta have been made, so at present the status quo for var robusta prevails.

A further option is from Spongberg ( Magnolias and their allies) who writes ‘…..it may be best to accord this plant cultivar status in the future’ – ie Magnolia sargentiana ‘Robusta’.

Whatever its name, it remains in my experience the best choice of the big flowered Asiatics for general cultivation: with vigorous growth, excessive freedom of flower, and weather resistant 8-10 inch nodding flowers in extraordinary profusion. A majestic tree.

I’ve sown seed from a M. sargentiana var robusta cultivar called ‘Blood Moon’ and produced two promising seedlings: M. ‘Premiere Cru’ and ‘Grand Cru’.

M. ‘Premiere Cru’, bred here at WHF, is striking for its intensely dark colour compared to its parent ( it may be pollinated by the deep pink Aberconway cultivar M. sprengeri ‘Claret Cup’ ). It is reliably hardy -and is certainly reliably free-flowering. Like an earlier seedling of var robusta, it flowered after 11 years from seed, and I like to think its robustness since then at White House Farm – very rarely damaged by frost in Kent – reflects its M. sargentiana var robusta tough constitution, which in my experience is by far the most ‘robust’ of all the early Asiatics. It’s high time to revise perceptions of the gardenworthiness of this first rank flowering tree.

Maurice Foster

Featured image at top: our M. sargentiana robusta ‘Caerhayes dark form’ in 2023.

Join us for our spring Open Days to see our 200+ magnolias, 140 camellias and other spring-blooming genera on Mother’s Day, Sunday March 30th and Wednesday April 9th. (£15). To reserve a space, email whitehousefarmarb@gmail.com